A compiler’s job is to translate one language into another. We use them in computer programming to transform the high-level languages that humans can read and write into something that computers understand.

For example, our source language might be C, which we can write, and our target language could be assembly, which our computers can run. Without a compiler, (or an assembler in the case that our target language is assembly), we would have to work with computer instruction sequences that lack the expressiveness that we’re used to in modern-day software development.

I won’t pretend to speak with any authority on compilers, but what I would like to do is share the baby steps I’ve taken into the fray by introducing the markdown to HTML compiler that I’m currently working on in Ruby.

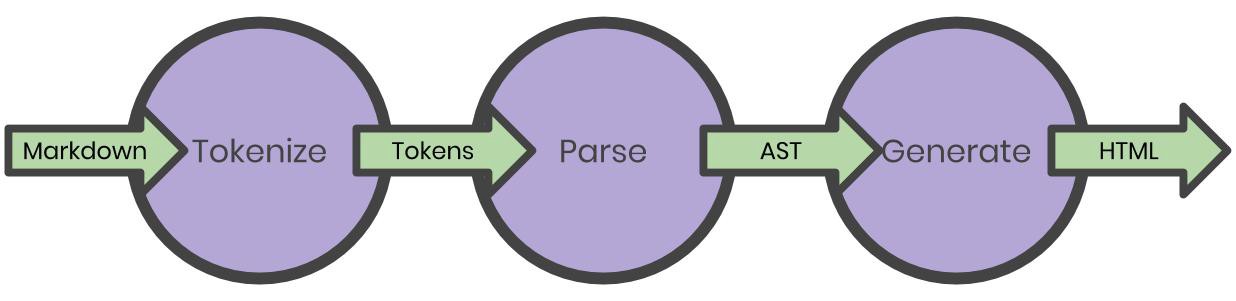

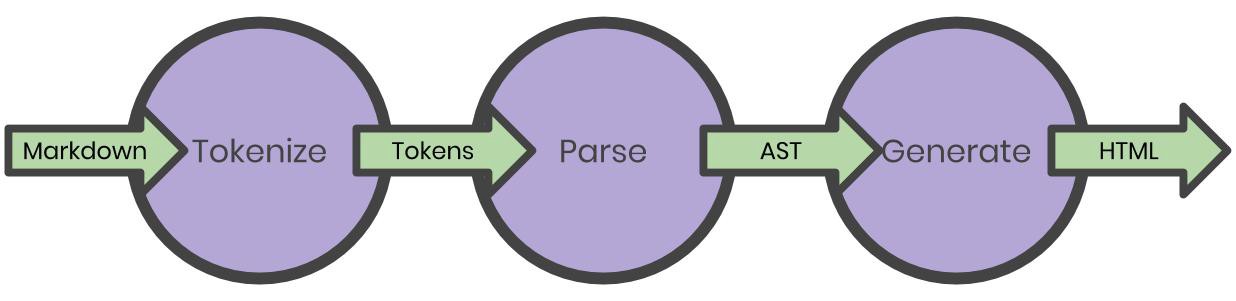

Of the most common compiler architectures that I’ve researched, at their core, they all seemed to have a few things in common: tokenizing, parsing, and target code emission.

Tokenizing is the act of scanning the source code character-by-character, and producing a list of tokens which contain metadata about the source code.

Parsing takes that list of tokens and creates a tree structure, specifically an abstract syntax tree. This tree represents the hierarchical structure of our source code and obfuscates any details about the source language’s syntax. It does this by following a set of rules know as the *grammar *of the language.

Finally, code emission turns the abstract syntax tree into the target language by walking the tree branch-by-branch, node-by-node.

Also know as scanning or lexing, this first step in our compiler is to turn the characters of our markdown into tokens.

You can think of a token as a character, or group of characters, with metadata or context related to what those characters represent in our source language. “Character” in our case means the literal character strings that are used to make up the code that we write.

Let’s say we write some source code:

a

It’s very simple, it just contains the character a. If we were to tokenize our code, we might get something like:

Tokenizer.scan("a")

=> #<type: :text, value: "a">

In this example, we’ve captured some metadata about the “code” that we wrote and began to attribute some context , :text, to it.